Heart Over Hard

“Doing hard things” has become a modern-day rally cry. Glennon Doyle turned it into a movement, and her message is spot on. But sometimes hard things aren’t about self-empowerment or shining brighter. Sometimes they’re about standing in the darkness with someone you love and singing your heart out.

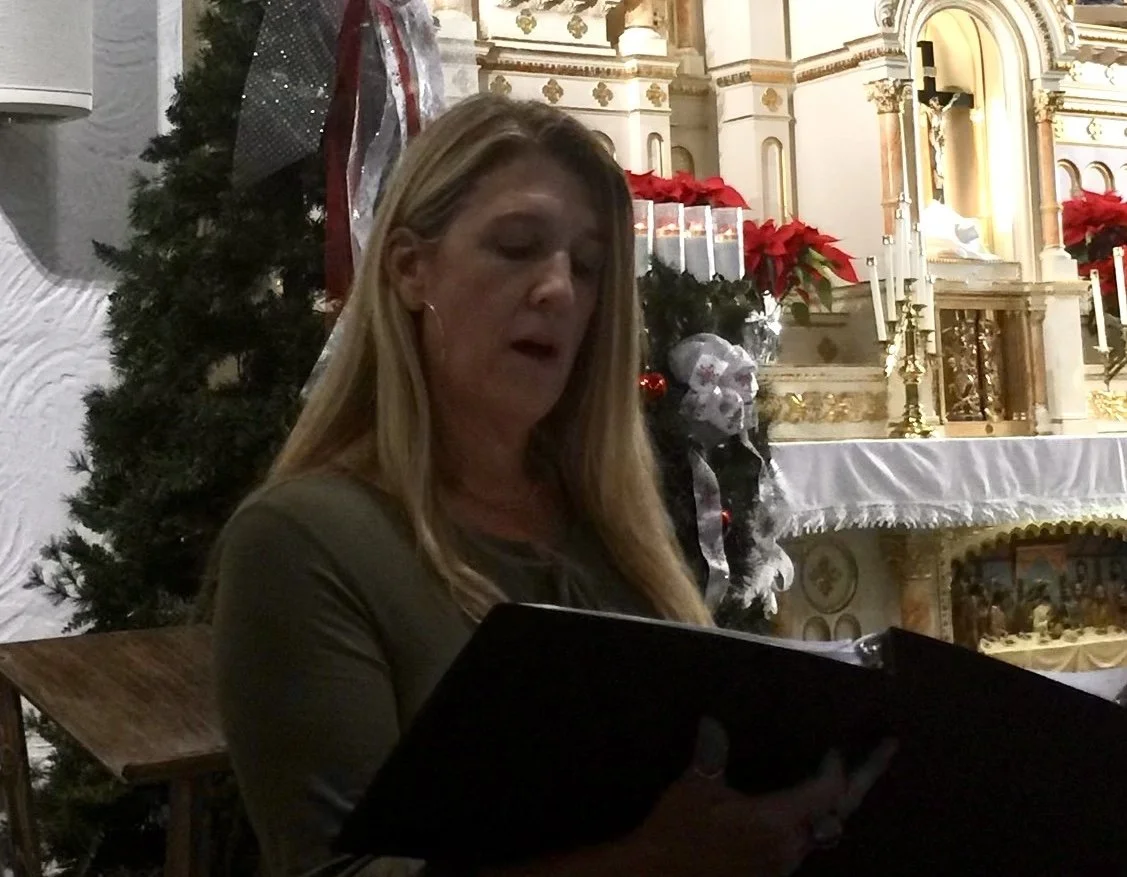

We’ve all had our share of “hard things,” and, as you can probably guess, mine typically entail my beloved family. The ones I’m focusing on today have to do with me singing at weddings and funerals of people I love.

Anyone who has followed my blog knows that my mom and dad taught their kids to offer it up. This was their Catholic cure-all for everything from heartbreak to head colds.

I think the only reason I can sing at a funeral for someone I love without dissolving into a puddle of tears is that I treat the moment as an offering. As Dad explained to us kids, doing something hard—or something you’d rather fake injury or illness to avoid—has the same spiritual physics as prayer. It creates comfort, courage, or a sense of connection.

Prayer is definitely what I needed when our family friend Richie asked me to sing at his wedding. Richie and his brother Randy had been our backyard neighbors growing up, practically honorary siblings to Julie and me. I was honored—until he handed me the song list.

“Wait. Is this the Groovy Kind of Love by Phil Collins?”

Why yes. It was indeed. It was their “special song.” Of course it was. And I wasn’t singing it at the reception, where a little wine and bad lighting could take the edge off. No. This was a church solo just before their vows.

What?

I froze. I wanted to vow not to sing unless we relocated to literally anywhere else—preferably a dark bar with poor acoustics.

Singing any part of that song makes me cringe, but delivering “anytime you want to, you can turn me onto anything you want to” from an altar? Come on. How would I ever keep a straight face?

Oh, and the accompaniment? A pipe organ.

What the?

As if that weren’t enough, when my sister Julie found out I had to sing that wretched song, she swore she’d sit front and center and do her best to stifle her laughter. She didn’t stifle anything. I couldn’t look directly at her without risking my own laughing fit. From my peripheral vision, I could see her hunched over and her shoulders shaking. So I avoided eye contact (or looking in her direction at all) and kept darting my gaze to the far left and right sides of the church. I’m sure I looked like a nervous spectator at Wimbledon.

I remember inhaling before the first line, wishing I had a paper bag over my head, while silently cheerleading myself along, “You can do this, Née. Just hold it together. And for the love of God, don't look at Julie."

Doing the hard thing in the moment of Richie’s wedding was uncomfortable, but it didn’t take me to my knees. It was a walk in the park compared to those times I’ve been asked to sing at a family member’s funeral.

Because my family means everything to me, getting through a song without crying or breaking down is actually insignificant compared to what simply singing the song means to the people counting on me. In these moments, the impossible tangle of grief and melody becomes my gift to them—an unspoken acknowledgment that they matter more than my discomfort.

Take Uncle Steve’s funeral. He was one of my favorite people in the whole world—funny, mischievous, and loving beyond measure. He made me feel special just for being born. The news of his death destroyed me.

The Divine Mercy Chaplet is a gorgeous prayer… when it’s not being sung in real time by someone trying not to cry, that is. Aunt Becky asked me to sing it at Steve’s wake. I was, of course, honored to be asked, especially knowing that Steve loved to hear me sing, yet singing at a family member’s wake or funeral requires me to conjure a strength so unlike any other that a big part of me dreads the request.

In the case of Uncle Steve, I ended up singing something that lasted long enough to test everyone’s faith. The song is supposed to have five verses—similar to the decades of a rosary—but I somehow managed to turn it into an endurance event and go a few decades beyond the customary five.

By about the seventh verse, I noticed the silhouette of Aunt Becky advancing from the side aisle like a defensive end about to tackle a running back. She stopped short of jumping onto the altar and gently gave me the universal “cut it” sign. I snapped out of my trance like a startled Brahmin priest. Suddenly, it made sense why Janet, seated next to me, had been staring at me for six straight minutes. To this day, I pray no one heard the inaudible curse words I whispered into the microphone after coming back into my body and realizing what I’d done.

Later, I learned that my Godson, Sean Patrick, was seconds away from pelting me in the head with a missalette if I didn’t shut up. At the reception, Aunt Jeanne confirmed what everyone else wished they had the guts to say, “That was beautiful, Née, but once in a lifetime is enough for your extended remix. Good grief. Where did you go?”

As we all laughed, I quietly decided that would be the end of my funeral singing career.

But I was wrong. A few months later, I stood at another microphone, offering it up again—this time for my little cousin who decided heaven was a better gig than this one.

Singing “Angel” by Sarah McLachlan at my little cousin Pete’s funeral might just be the Queen Mother of my hard things. The moment Uncle Domenic mentioned the title, my brain screamed Noooooo, while my mouth said, “Of course, dear uncle. I’d be honored to.” I hung up the phone from that call and wept—both from the loss of Peter Anthony, and because I had no clue how I was going to keep it together singing that heart-wrenching song. Every time I rehearsed, the lyrics stung so deep I couldn’t keep going. They aligned perfectly with how I imagined Pete must have felt in the moments just before he left us. And because of the vivid image my mind replayed of him finally at peace in the arms of the angel, far away from here, I would cry uncontrollably, breathe, and rehearse it again.

Thankfully, miracles often seem to be on my side. And I experienced one on the day of the funeral. I sang Angel with the certainty of Sarah herself, knowing that my melodic tribute meant the world to people who meant the world to me.

That’s the thing about hard things. You do them because love asks you to. You choke down the grief. You sing through the lump in your throat. You keep going. The people we love deserve our capacity to rise above discomfort—whether it’s being asked to sing Groovy Kind of Love with a straight face, do everything in your power to keep a primal sob at bay so you can make it through a Sarah McLachlan ballad, or to gracefully recover from your grief-strickenness that accidentally turns a wake into a marathon musical.

We all have our own versions of these moments—when love corners us and asks, “Can you hold it together for me, just this once?” And somehow, even when our knees shake and our voices break, we do.

Love doesn’t care if our voices crack. It only asks that we show up.